Life in the Mamluk Sultanate

featuring Joshua White, Zoe Griffith, Amina Elbendary, and Kristina Richardson

| Military slavery was critical to the function of most imperial states in the medieval Islamic world. But in a moment of crisis during the 13th century, the cadre of enslaved military personnel or mamluks employed by the Ayyubid dynasty in Egypt overthrew that dynasty, establishing their own sultanate that governed Egypt, Syria, and the Hijaz for more than two centuries.

In this episode, we're examining the making of the Mamluk Sultanate and life in its capital of Cairo. We discuss the institutions and structures established in the city of Cairo as displays of power and charity by Mamluk elite, and we consider the role of urban protest and contention between the streets and the citadel as an integral facet of politics in Mamluk cities. We also shed light on the little-studied community of Ghurabā' who lived on the city's margins and engaged in one of the earliest examples of printing in the Islamic world.

Military slavery was critical to the function of most imperial states in the medieval Islamic world. But in a moment of crisis during the 13th century, the cadre of enslaved military personnel or mamluks employed by the Ayyubid dynasty in Egypt overthrew that dynasty, establishing their own sultanate that governed Egypt, Syria, and the Hijaz for more than two centuries.

In this episode, we're examining the making of the Mamluk Sultanate and life in its capital of Cairo. We discuss the institutions and structures established in the city of Cairo as displays of power and charity by Mamluk elite, and we consider the role of urban protest and contention between the streets and the citadel as an integral facet of politics in Mamluk cities. We also shed light on the little-studied community of Ghurabā' who lived on the city's margins and engaged in one of the earliest examples of printing in the Islamic world.

"The Making of the Islamic World" is an ongoing series aimed at providing resources for the undergraduate classroom. The episodes in this series are subject to updates and modification.

|

Joshua M. White is Associate Professor of History at the University of Virginia. He is the author of Piracy and Law in the Ottoman Mediterranean (Stanford University Press, 2017). |

|

Zoe Griffith is Assistant Professor of History at Baruch College, CUNY and completed her Ph.D. at Brown University in 2017. Her research focuses on political economy, law, and governance in the Ottoman Arab provinces from the 17th to the 19th centuries. She records mainly in New York City. |

|

Amina Elbendary is an associate professor of Arab and Islamic civilizations at The American University in Cairo, where she teaches courses on early and medieval Islamic history, Muslim political thought and social and cultural history of the Arab Muslim world. She is the author of Crowds and Sultans: Urban Protest in Late Medieval Egypt and Syria. |

|

Kristina Richardson is Associate Professor of History at Queens College and the CUNY Graduate Center. She is the author of Difference and Disability in the Medieval Islamic World (Edinburgh University Press, 2012) and Gypsies in the Medieval Islamic World: A History of the Ghurabā’, forthcoming with Bloomsbury Publishers. |

Credits

Interviews by Chris Gratien

Sound production by Chris Gratien

Transcript by Marianne Dhenin

Music (by order of appearance): Aitua - The Grim Reaper - I Andante; Chad Crouch - Traction; Zé Trigueiros - Sombra; A.A. Aalto - Admin; Zé Trigueiros - Big Road of Burravoe; Chad Crouch - Wide Eyes; Aitua - Volcano; A.A. Aalto - Entonces; Chad Crouch - Coral; A.A. Aalto - Canyon

Explore

The Mamluk Sultante was founded in Cairo in 1250 and lasted for more than 200 years until the Ottoman conquest in 1517. Despite internal conflict, the state the Mamluks presided over was quite stable. The Mamluk Sultanate was unique among the states we've talked about in this series because it was never really ruled by a single dynasty. Rather, it was the self-replication of the Mamluk system (first the predominantly Turkic "Bahri" Mamluks and later the predominantly Circassian "Burji" Mamluks) that ran the state. The Mamluk Sultanate was also unique in that its first ruler during the overthrow of the Ayyubids was a former concubine, Shajar al-Durr, who for a brief period was the sovereign of the Sultanate, even minting gold dinar in her own name.

The Mamluks left a large architectural imprint in Cairo, which at its height was one of the largest cities of the medieval world. Mamluk mosque and tomb complexes often housed schools, hospitals, soup kitchens, and other charitable institutions. On the Ottoman History Podcast, we interviewed Ahmed Ragab about the history of these medieval Islamic hospitals and the activities that took place there. On a smaller level, neighborhood sabil-kuttab structures patronized by the Mamluk elite provided drinking water and basic education in the city.

The Mosque-Madrasa complex of Sultan Hassan in Cairo. Source: Wikipedia / Mohammed Moussa

The city was a site of constructing Mamluk legitimacy, but it was also the site of contention between the ruling class and different elements of urban society. In our podcast, we spoke to Amina Elbendary about the various types of protests and riots that occurred in Mamluk Cairo. Protest was a consistent feature of the social dynamic in the city. From the market to the mosque, residents of medieval Cairo used collective action to make their grievances known to the Sultan. Through the lens of protest, we see which issues really mattered to Cairenes of the period and which dimensions of Mamluk rule were most contentious. But as Elbendary noted, protest was not merely a sign of instability or failure on the part of the Mamluk rulers. It was also an integral component of how Mamluk rule over the sultanate's various constituents was constructed.

The Mamluk Sultanate was home to a vibrant intellectual life. Thanks to writers like bureaucrat-cum-scholar Shihab al-Din al-Nuwayri, we know a great deal about the function of the Mamluk state. Excerpts of Al-Nuwayri's compendium entitled The Ultimate Ambition in the Arts of Erudition have been beautifully translated by Elias Muhanna and make a fantastic companion to this podcast. They detail much more than various facets of life in the Mamluk Sultanate; they encompass al-Nuwayri's exhaustive investigations into the extent of human knowledge during his time.

To enjoy some of Elias Muhanna's favorite passages from The Ultimate Ambition in the Arts of Erudition, we recommend our interview from 2016.

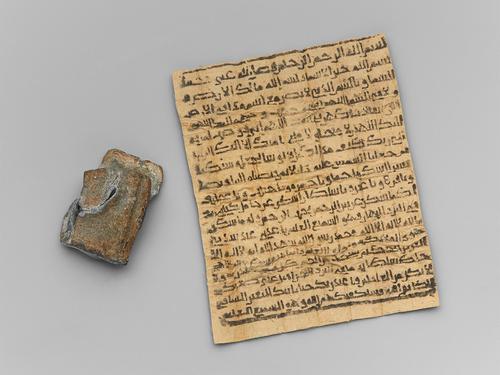

Despite the many great figures in the history of Arabic letters and science who lived under Mamluk rule, in the podcast, we directed our attention to the intellectual output of a lesser-known group known as the Ghuraba. As our guest Kristina Richardson explained, the Ghuraba were members of a broader Romani diaspora often referred to by the label of Gypsies. The Ghuraba neighborhood of Mamluk Cairo was located in what is now the downtown of the modern city. The Ghuraba were involved in various professions ranging from entertainment to medical care, and though this community has often been associated with illiteracy, they in fact dominated the block-printing industry of medieval Cairo.

A printed amulet dating to 11th century Egypt. Source: Aga Khan Museum

The history of the Ghuraba is just one example of the wealth of social and cultural history of the medieval Islamic world still waiting to be explored by scholars. To get going on your own explorations of the Mamluk Sultanate, we recommend this short bibliography below as a starting point.

Textile Fragment with Mamluk Emblem. Source: Met Museum

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Amitai, Reuven. “Diplomacy and the Slave Trade in the Eastern Mediterranean: A Re-Examination of the Mamluk-Byzantine-Genoese Triangle in the Late Thirteenth Century in Light of the Existing Early Correspondence.” Oriente Moderno, Nuova serie, 88, no. 2 (2008): 349–68.

Ayalon, David. Gunpowder and Firearms in the Mamluk Kingdom: A Challenge to Medieval Society (1956), 2016.

Bauden, Frédéric, and Malika Dekkiche. Mamluk Cairo, a Crossroads for Embassies: Studies on Diplomacy and Diplomatics. 2019.

Bauer, Thomas. “Mamluk Literature: Misunderstandings and New Approaches.” Mamluk Studies Review 9, no. 2 (2005): 105-32.

Behrens-Abouseif, Doris. The Book in Mamluk Egypt and Syria (1250-1517): Scribes, Libraries and Market. BRILL, 2018.

_____. Cairo of the Mamluks: a history of the architecture and its culture, London: IB Taurus, 2007.

Berkey, Jonathan. The Transmission of Knowledge in Medieval Cairo: A Social History of Islamic Education. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992.

Chamberlain, Michael. Knowledge and Social Practice in Medieval Damascus, 1190-1350. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Christ, Georg. Trading Conflicts: Venetian Merchants and Mamluk Officials in Late Medieval Alexandria. BRILL, 2012.

Elbendary, Amina. Crowds and Sultans: Urban Protest in Late Medieval Egypt and Syria. 2017.

Guo, Li. “Mamluk Historiographic Studies: The State of the Art.” Mamluk Studies Review 1 (1997): 15-43.

Holt, Peter Malcolm. Early Mamluk Diplomacy, 1260-1290: Treaties of Baybars and Qalāwūn with Christian Rulers. BRILL, 1995.

Irwin, Robert. The Middle East in the Middle Ages: The Early Mamlūk Sultanate 1250-1382. London: Croom Help, 1986.

Lapidus, Ira M. Muslim Cities in the Later Middle Ages. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967.

Muhanna, Elias. World in a Book: Al-Nuwayri and the Islamic Encyclopedic Tradition. Princeton University Press, 2019.

Nasrallah, Nawal. Treasure Trove of Benefits and Variety at the Table: A Fourteenth-Century Egyptian Cookbook. Leiden: Brill, 2020.

Northrup, Linda S. From Slave to Sultan: The Career of al-Manṣūr Qalāwūn and the Consolidation of Mamluk Rule in Egypt and Syria (678-689 A.H. / 1279-1290 A.D.). Stuttgart F. Steiner, 1998.

Petry, Carl F. The Civilian Elite of Cairo in the Later Middle Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981.

_____. The Cambridge History of Egypt. Vol. 1 - Islamic Egypt, 640-1517. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Philipp, Thomas and Ulrich Haarmann, eds. The Mamluks in Egyptian Politics and Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Rapoport, Yossef. “Women and Gender in Mamluk Society – an Overview”, Mamlūk Studies Review (link is external), 11, 2 (November 2007), 1-45.

Richardson, Kristina L. Difference and Disability in the Medieval Islamic World: Blighted Bodies. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2014.

Tsugitaka, Sato. State and Rural Society in Medieval Islam: sultans, muqata'as, and fallahun, Leiden: Brill, 1997.

|

Chris Gratien is Assistant Professor of History at University of Virginia, where he teaches classes on global environmental history and the Middle East. He is currently preparing a monograph about the environmental history of the Cilicia region of the former Ottoman Empire from the 1850s until the 1950s. |

Comments

Post a Comment

Due to an overwhelming amount of spam, we no longer read comments submitted to the blog.