Turkino

Episode 411

with additional contributions by Devi Mays, Claudrena Harold, Victoria Saker Woeste, Sam Negri, and Louis Negri

Feed | iTunes | GooglePlay | SoundCloud

Leo lived in New York City with his family. Born and educated in the cosmopolitan Ottoman capital of Istanbul, he was now part of the vibrant and richly-textured social fabric of America's largest metropolis as one one of the tens of thousands of Sephardic Jews who migrated to the US. Though he spoke four languages, Leo held jobs such as garbage collector and shoeshine during the Great Depression. Sometimes he couldn't find any work at all. But his woes were compounded when immigration authorities discovered he had entered the US using fraudulent documents. Yet Leo was not alone; his story was the story of many Jewish migrants throughout the world during the interwar era who saw the gates closing before them at every turn. Through Leo and his brush with deportation, we examine the history of the US as would-be refuge for Jews facing persecution elsewhere, highlight the indelible link between anti-immigrant policy and illicit migration, and explore transformations in the history of race in New York City through the history of Leo and his family.

This episode is part of our investigative series Deporting Ottoman Americans.

This episode is part of our investigative series Deporting Ottoman Americans.

Stream via SoundCloud

Explore the Sources

Sephardic Diaspora

|

| Sephardic migrants in Argentina: Jacobo Bibas with his wife Mesodi Tobelem and their children Simi, Estrella, León, Esther and Jaime, from Misiones Province, circa 1900. Source: Wikipedia |

The history of the Sephardic community is indelibly linked to the history of America. It was forged in the fateful year of 1492, when Spain took its first step towards conquest in the Americas with the Columbian voyages and at the same time enacted the Alhambra decree, which compelled Jews and Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula to convert or flee. The Jewish communities expelled from Spain formed communities throughout the Mediterranean. They maintained a unique identity and a language known as Judeo-Spanish or Ladino as they formed networks that straddled the states of the Mediterranean. For more, listen to our interview with historian Sarah Stein.

With the great waves of migration during the late 19th and early 20th century, Sephardic Jews set out once again, this time for the Americas--not just the United States--but also countries in Latin America like Mexico, Cuba, and Argentina where they already spoke a version of the lingua franca. In the interview below, Devi Mays explores how their unique Iberian heritage sometimes benefited Sephardic Jews in their experience of global migration. Although Jews were increasingly targeted for immigration restriction, Sephardic Jews could draw on their Iberian and Middle Eastern heritage in different ways in order to blend while navigating different settings.

With the great waves of migration during the late 19th and early 20th century, Sephardic Jews set out once again, this time for the Americas--not just the United States--but also countries in Latin America like Mexico, Cuba, and Argentina where they already spoke a version of the lingua franca. In the interview below, Devi Mays explores how their unique Iberian heritage sometimes benefited Sephardic Jews in their experience of global migration. Although Jews were increasingly targeted for immigration restriction, Sephardic Jews could draw on their Iberian and Middle Eastern heritage in different ways in order to blend while navigating different settings.

In the diaspora, Sephardic Jews became a small minority within a much larger Jewish diaspora. Our specialist consultant in this episode historian Devin Naar has explored how those who came from the Ottoman Empire sometimes adopted the label of turkino, which was equated with Ottoman citizenship in the Ladino language and reflected this subset of the Jewish diaspora's geographical ties to Turkey. For the American press, the supposed hybridity of this community was sometimes the source of curiosity. The image below from an article in the New York Tribune contains a profile of New York's many thousands "Jews who know no Yiddish," Ladino and Arabic speaking Jews who lived in Manhattan between the Italian and Ashkenazi neighborhoods and worked jobs like shoeshine and candy-seller.

Our protagonist Leo Negri himself became the subject of a similar such article (see below) that ran in papers throughout the country. In 1935, he showed up in court to testify in a domestic abuse case, only to be dismissed by the magistrate, who found the identities of the defendant, plaintiff, and witnesses too bewildering for his jurisdiction. But in the pages of the New York-based Ladino newspaper La America, the intra-communal tensions within New York's Jewish community were also explored. The Ashkenazi majority often looked down on groups like the Turkinos for their apparent non-European culture.

The history of Sephardic Jews in America has often been overshadowed by the history of the much larger Ashkenazi minority, but the Sephardic Studies program at University of Washington's Strom Center for Jewish Studies is one institution that is working to bring to light the experience of the Sephardic diaspora through digitization efforts and public history projects. Learn about the Sephardic Studies program on the University of Washington website.

|

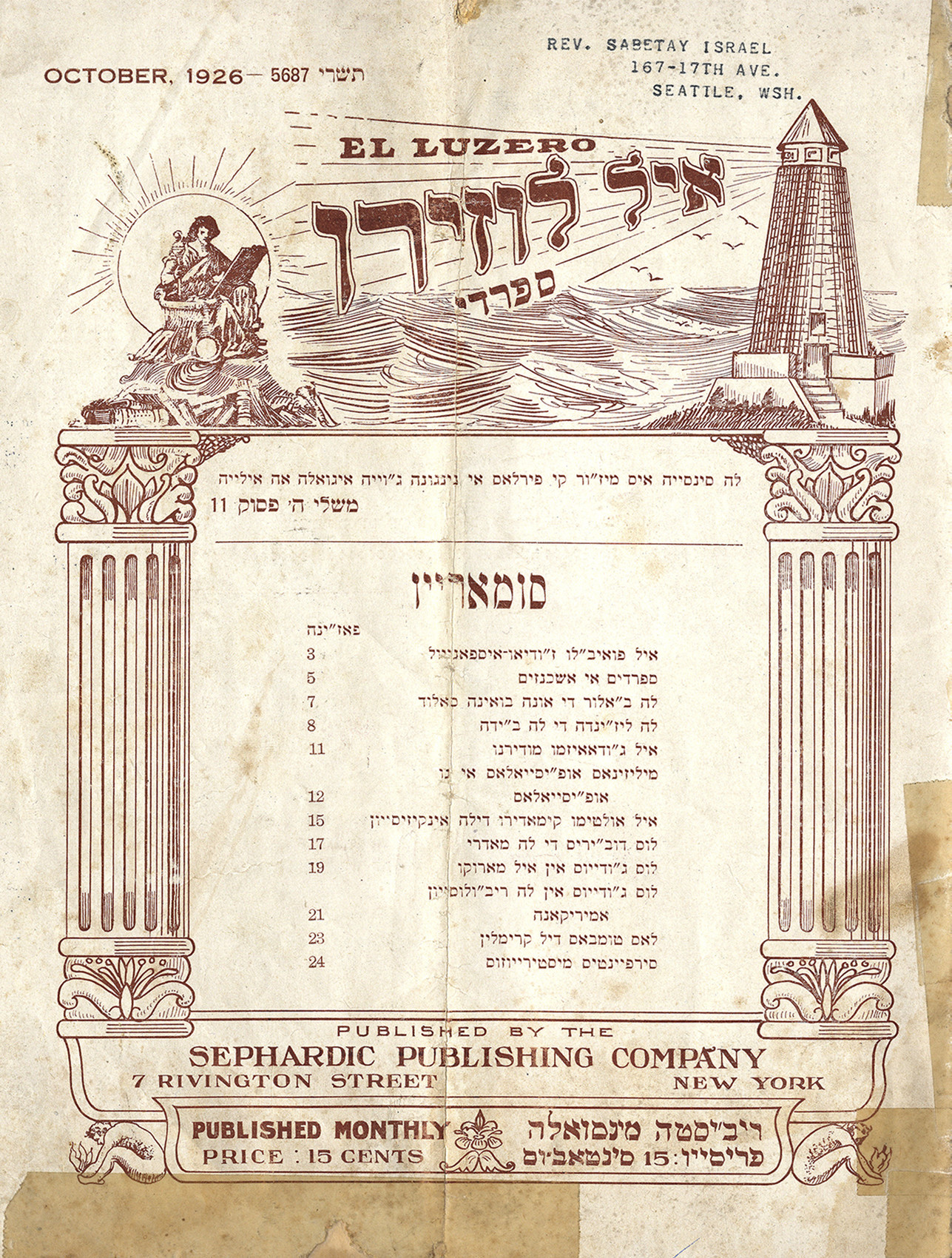

| Cover of El Luzero magazine, 1926. Source: Strom Center for Jewish Studies |

|

| A 1912 article in the New York Tribune profiled the Sephardi and Mizrahi communities of Manhattan. It portrayed them as inhabitants of a small, isolated enclave of migrants with little integration into the social fabric of New York. But facts listed in the article such as the rise in naturalization among this community call this characterization into question. Source: Library of Congress |

|

| Leo Negri made his newspaper debut in 1935 as a witness in a domestic abuse case. The details were published when the magistrate dismissed the case and the apparently hybrid identities of the individuals involved. Source: Republican and Herald 10 January 1935 via Newspapers.com |

Global Anti-Semitism

During the 1920s, a nativist backlash against the political transformation and social mobility of African-Americans and immigrant groups like Jews manifested in a variety of forms, including the eugenics movement and racially-biased immigration quotas explored throughout our series. For an introduction to the history of eugenics in the United States, listen to our interview with historian Sarah Milov.

Much of the anti-immigration animus in the United States was linked to anti-Semitism, as millions of

Jews had settled in the country over prior decades. One of the foremost proponents of this trend was also one of the richest men in America: Henry Ford. Ford circulated articles containing anti-Semitic rhetoric in a series called "The International Jew," which reached hundreds of thousands of Americans through the Dearborn Independent, a newspaper Ford acquired and distributed through his automotive sales network. "The International Jew" would and international audience during the 1920s, including in Germany, which was in the midst of the rise of Nazism. Ford was sued over the Dearborn Independent affair. You can learn more by listening to our interview with Victoria Saker Woeste.

During the interwar period, Jews faced increased barriers to immigration even as anti-Semitism and anti-Jewish violence were on the rise. This combination created a large number of European Jews who ended up as undocumented immigrants in the United States and throughout Latin America. Libby Garland's After They Closed the Gates: Jewish Illegal Immigration to the United States, 1921-1965 is an excellent investigation of the barriers prospective Jewish migrants and later refugees of the Holocaust faced in coming to the United States before the immigration reform of the 1960s.

American government and public opinion regarding openness to European refugees such as Jewish Holocaust survivors did not begin to change until after World War II. During the interwar period, as the persecution of Jews in Nazi Germany and the eventual horrors of the Holocaust unfolded, the United States played an ambivalent role. While some Americans responded with alarm, others continued to voice anti-Semitic and anti-immigrant opinions. Many vocally sympathized with Nazism. American immigration policy continued to restrict Jewish immigration, even into the war years. Many European Jews who fell victim to the Holocaust had been waiting for American visas, which took years to obtain in many cases. For a collection of images and documents related to the subject, see the "Americans and the Holocaust" exhibit on the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum website.

Turkey, as the successor to the Ottoman Empire, continued to be a home for the Sephardic community. But the Turkish nation-state project of the 1920s and 30s suddenly cast the longtime residents of Turkey as unwelcome guests due to their having maintained their unique language and religion. The height of interwar anti-Semitism in Turkey manifested in the pogroms of Thrace in 1934. As a result of these incidents, Thrace's Jewish inhabitants evacuated to Istanbul. The old Jewish quarter of Edirne was left in ruins. During the interwar period, many Jews of Turkish nationality left for the Americas. More would leave for Israel after its foundation in 1948.

Despite an increasingly hostile environment, Jews who had remained in Turkey were largely shielded from the horrors of the Holocaust due to Turkey's remaining neutral during the Second World War. But their counterparts in cities like Thessaloniki in Greece were among the often forgotten victims of the Holocaust. During the Nazi occupation of Greece, the Greek Sephardic community was all but annihilated. For more on the experience of formerly Ottoman Jews in Greece, listen to our interview with historian Devin Naar.

Deporting Leo

|

| Leo Negri's deportation file included his original Ottoman identity papers. The image above was (probably) taken of Leo in Istanbul while he was in his late teens. |

Leo Negri entered the United States with a fake Cuban passport in 1928. By 1936, he was a father of three and married to a native-born American woman named Flora Gadol. His first deportation hearing in 1936 and would have a number of other meetings with INS as he fought his deportation case. The interrogations of his hearings themselves are detailed accounts of Leo's movements and struggles with employment over the years.

Part of the difficulty in deporting Leo was obtaining a passport with which he could travel. Leo was a Turkish national, but there was no documentary evidence of this fact. He had left his Ottoman identity papers and Turkish passport in Cuba. Remarkably, US diplomats were able to locate the documents years later and attempted to use them to convince the Turkish government to issue a new passport for Leo.

|

| A portrait of Leo c1936 from his deportation file. |

|

| A page from the deportation hearings of Leo Negri |

Brooklyn Bittersweet

During the 1960s, the socioeconomic and demographic composition of many American cities was changing rapidly. Wendell Pritchett's Brownsville, Brooklyn: Blacks, Jews, and the Changing Face of the Ghetto is a detailed study of this phenomenon in a neighborhood of New York City. During the late 19th century, Brownsville emerged as a vibrant Jewish immigrant neighborhood that developed a strong progressive tradition. Leo Negri and his family lived there during the 1940s, when the neighborhood began to change. Post-WWII migration to New York City brought new African-American and Puerto Rican residents to Brownsville. With white flight to the suburbs during 1960s, Brownsville changed even more rapidly.

The 99% Invisible podcast episode "Turf Wars of East New York" explores how this region of Brooklyn became a flashpoint for conflict when an increasingly embattled Italian-American and Jewish-American minority remained and some fought against the integration and change of their neighborhood. Brownsville and East New York saw a rise in crime, and in July 1966, a small group of young white men from the neighborhood who called themselves SPONGE sparked a riot during one of their hate-filled demonstrations against the changing makeup of the neighborhood. An eleven-year-old African-American boy named Eric Dean was killed in the tumult. The actual shooter was never identified, but Mayor John Lindsay tried to contain the fallout by increasing the police presence in the neighborhood.

In January 1967, Leo and his wife Flora were out late visiting relatives in East New York. On their way to catch a bus back to Coney Island, they were accosted by a group of young men, who tried to take Flora's purse. Leo tried to fend them off, and as he and Flora attempted to board a bus, one of them shot Leo, inflicting a fatal wound. Police and journalists swarmed the scene. Leo would die of his wounds on the floor of the bus. Reader be warned, if you Google his name today, chilling photographs licensed by Getty Images are readily available online. The killing received a large amount of press and was politicized by those who saw the random killing as having a racial dimension. The gunman was an eighteen-year-old African-American Brooklyn resident, and Leo Negri was portrayed in the press as an innocent white victim of New York's escalating crime problem. Innocent and unsuspecting though he was to be sure, it was paradoxical for a man from a group previously targeted for discriminatory immigration policies to be claimed as white only in death by those who lamented the transformation of New York neighborhoods. In the newspaper articles below, you can explore how the press covered the killings of Eric Dean and Leo Negri.

|

| Coverage of the killing of Eric Dean and its aftermath during the riots in East New York. Source: New York Daily News 23 July 1966 via Newspapers.com |

|

| While some news outlets took the police investigation of the killing of Eric Dean at face value, others wrote critically of the Republic Mayor John Lindsay's handling of the incident. This article syndicated from the Village Voice profiles the alleged shooter, listing the numerous problems with the accusations against him. The alleged shooter was not convicted. Source: The Gazette and Daily, York, PA via Newspapers.com |

|

| Digitized newspaper collections make it easier to see the media spin of Leo's killing in real time. On the left is an article syndicated from the Associated Press and published in the Clarion Ledger of Jackson, Mississippi. On the right is the same article with a different title as published in The Times and Democrat of Orangeburg, South Carolina. via Newspapers.com |

|

| The Daily Oklahoman, 9 January 1967 via Newspapers.com |

|

| While the killing of Leo Negri was well publicized, there was comparatively little press coverage, especially beyond New York City, of the trial of his shooter. Source: New York Daily News, 10 January 1967 via Newspapers.com |

Credits

|

Chris Gratien, Producer and Host Chris Gratien is Assistant Professor of History at University of Virginia, where he teaches classes on global environmental history and the Middle East. He is currently preparing a monograph about the environmental history of the Cilicia region of the former Ottoman Empire from the 1850s until the 1950s. |

|

Devin Naar, Episode Consultant Devin Naar is the Isaac Alhadeff Professor in Sephardic Studies and Associate Professor of Jewish Studies and History at the University of Washington in Seattle, where he directs the Sephardic Studies Program. Naar received his PhD in History from Stanford University, served as a Fulbright Scholar in Greece, and sits on the Academic Advisory Council of Center for Jewish History in New York. |

|

Sam Dolbee, Script Editor Sam Dolbee is a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University's Mahindra Humanities Center. He completed his PhD in 2017 at NYU in History and Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies. He works on the environmental history of the Jazira region in the late Ottoman and post-Ottoman periods. |

|

Emily Pope-Obeda, Series Consultant Emily Pope-Obeda received her PhD in History in 2016 from the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign. She spent the 2016-2017 academic year as a Visiting Fellow at the James Weldon Johnson Institute for the Study of Race and Difference at Emory University. She is currently a lecturer in the History and Literature program at Harvard University, where she working on a book manuscript on the American deportation system during the 1920s. |

Featured Contributors

|

Devi Mays is Assistant Professor of Judaic Studies at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor and Fellow at the Frankel Institute for Advanced Judaic Studies. After receiving her Ph.D. in Jewish History from Indiana University in 2013, she was awarded a Postdoctoral Fellowship in Modern Jewish Studies at the Jewish Theological Seminary. She has published in Mashriq and Mahjar: Journal of Middle East Migration Studies, and has translated for Sephardi Lives: A Documentary History, Julia Phillips Cohen and Sarah Abrevaya Stein, ed. (Stanford UP, 2014). Her work has appeared in several edited collections, including World War I and the Jews (Berghahn Books, 2017), and Jews and the Mediterranean (Indiana University Press, forthcoming). She is currently revising a book manuscript, tentatively entitled Forging Ties, Forging Passports: Migration and the Modern Sephardi Diaspora.

|

|

Claudrena Harold is a professor of African American and African Studies and History at University of Virginia. In 2007, she published her first book, The Rise and Fall of the Garvey Movement in the Urban South, 1918-1942. In 2013, the University of Virginia Press published The Punitive Turn: New Approaches to Race and Incarceration, a volume Harold coedited with Deborah E. McDowell and Juan Battle. Her latest monograph is New Negro Politics in the Jim Crow South, which was published by the University of Georgia Press.

|

|

Victoria Saker Woeste was educated at the University of Virginia (B.A. 1983) and the University of California at Berkeley (M.A. 1985, Ph.D. 1990). Since 1994 she has been a member of the research faculty at the American Bar Foundation in Chicago, where she specializes in U.S. legal history and writes about political economy, hate speech, antisemitism, and modern American political conservatism. |

|

Sam Negri was born in Coney Island in 1941. He moved from his home in New Haven, CT to Tucson, Arizona in 1972. He worked as a newspaper and magazine writer/reporter for 40-plus years and is the author of several books on Arizona-related themes. He is married to Pat Negri and has three children, six grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

|

|

Louis Negri is an accomplished watercolor painter and teacher.

|

Episode No. 411 (DOAP No. 3)

Release Date: 2 May 2018

Script, narration, and audio editing by Chris Gratien

Chief Consultant: Emily Pope-Obeda

Episode Consultant: Devin Naar

Script Editor: Sam Dolbee

Additional contributions by Devi Mays, Claudrena Harold, Victoria Saker Woeste, Sam Negri, and Louis Negri

Many thanks to Chris Silver, Shireen Hamza, and Reem Bailony

Digitized Sephardic music recordings (Me vo muerir | Vayered Ashem) published on Sephardic Music by Joel Bressler.

Special thanks to Sara Afonso for use of "The Asylum" and "Tears from Mars"

Additional Audio Elements (by order of first appearance): "Julia's Theme" by Chris Gratien; NYC Metro (recorded by Chris Gratien); "Sombra" by Zé Trigueiros; DOAP Main Beat; Zé Trigueiros - Big Road of Burravoe; "Blen Blen Blen" by Hotel Nacional Orchestra; DOAP Piano Interlude 1 by Chris Gratien; DOAP Interlude 2 by Chris Gratien; "Fast" by Zé Trigueiros; American Jewish Hour "Bridegroom Special"; Paul Whiteman with Johnny Hauser - Gloomy Sunday; The New York Central in 1928-1929; Muhyiddin Bayun - Taxim Alal Wahidat; Keler Tsoler (Komtias) by Perspectives Ensemble; Charlie Dubin And Orchestra; Lou Parker - Gypsy Mood No. 5; "Misirlou" by Jan August; John F. Kennedy ADL Address, 'We Are A Nation of Immigrants'; "Clair De Lune (Moonlight)" performed by Sula Levitch; Nemeton - Sequestration; "Devasted Area"; Zé Trigueiros - Chiaroscuro.

Release Date: 2 May 2018

Script, narration, and audio editing by Chris Gratien

Chief Consultant: Emily Pope-Obeda

Episode Consultant: Devin Naar

Script Editor: Sam Dolbee

Additional contributions by Devi Mays, Claudrena Harold, Victoria Saker Woeste, Sam Negri, and Louis Negri

Many thanks to Chris Silver, Shireen Hamza, and Reem Bailony

Digitized Sephardic music recordings (Me vo muerir | Vayered Ashem) published on Sephardic Music by Joel Bressler.

Special thanks to Sara Afonso for use of "The Asylum" and "Tears from Mars"

Additional Audio Elements (by order of first appearance): "Julia's Theme" by Chris Gratien; NYC Metro (recorded by Chris Gratien); "Sombra" by Zé Trigueiros; DOAP Main Beat; Zé Trigueiros - Big Road of Burravoe; "Blen Blen Blen" by Hotel Nacional Orchestra; DOAP Piano Interlude 1 by Chris Gratien; DOAP Interlude 2 by Chris Gratien; "Fast" by Zé Trigueiros; American Jewish Hour "Bridegroom Special"; Paul Whiteman with Johnny Hauser - Gloomy Sunday; The New York Central in 1928-1929; Muhyiddin Bayun - Taxim Alal Wahidat; Keler Tsoler (Komtias) by Perspectives Ensemble; Charlie Dubin And Orchestra; Lou Parker - Gypsy Mood No. 5; "Misirlou" by Jan August; John F. Kennedy ADL Address, 'We Are A Nation of Immigrants'; "Clair De Lune (Moonlight)" performed by Sula Levitch; Nemeton - Sequestration; "Devasted Area"; Zé Trigueiros - Chiaroscuro.

Further Reading

Ben-Ur, Aviva. Sephardic Jews in America: A Diasporic History. New York, N.Y.: New York University Press, 2012.

Garland, Libby. After They Closed the Gates: Jewish Illegal Immigration to the United States, 1921-1965. 2018.

Harold, Claudrena. New Negro Politics in the Jim Crow South. University of Georgia Press, 2018.

Hester, Torrie. Deportation: The Origins of U.S. Policy. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017.

Kanstroom, Dan. Deportation Nation: Outsiders in American History. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2010.

Khater, Akram Fouad. Inventing Home: Emigration, Gender, and the Middle Class in Lebanon, 1870-1920. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

Moloney, Deirdre M. National Insecurities: Immigrants and U.S. Deportation Policy Since 1882. Univ Of North Carolina Pr, 2016.

Naar, Devin E. Jewish Salonica: Between the Ottoman Empire and Modern Greece. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2017.

Naar, Devin E. 2015. "Turkinos beyond the Empire: Ottoman Jews in America, 1893 to 1924". Jewish Quarterly Review. 105, no. 2: 174-205.

Ngai, Mae M. Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 2014.

Pope-Obeda, Emily. "When in Doubt, Deport!": U.S. Deportation and the Local Policing of Global Migration During the 1920s (Ph.D. Thesis). University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, 2016.

Pritchett, Wendell. Brownsville, Brooklyn: Blacks, Jews, and the Changing Face of the Ghetto. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2003.

Stein, Sarah Abrevaya. Extraterritorial Dreams: European Citizenship, Sephardi Jews, and the Ottoman Twentieth Century. 2017.

Zolberg, Aristide R. A Nation by Design: Immigration Policy in the Fashioning of America. 2008.

Comments

Post a Comment

Due to an overwhelming amount of spam, we no longer read comments submitted to the blog.